Laser breakthrough sets the stage for new X-ray science possibilities

The technique could improve how scientists study materials and drive advancements in high-performance technologies, such as next-generation computer chips.

A team led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have generated a highly exotic type of light beam, called a Poincaré beam, using the FERMI free-electron laser (FEL) facility in Italy, marking the first time such a beam has been produced with a FEL. The technique could improve how scientists study materials and drive advancements in high-performance technologies, such as next-generation computer chips. The results were published today in Nature Photonics.

SLAC scientistIt’s exciting to think about what researchers will do with this.

“This is a significant step forward,” said SLAC scientist and collaborator Erik Hemsing. “Poincaré beams allow us to probe materials in new ways, capturing complex behaviors in one pulse. It’s exciting to think about what researchers will do with this.”

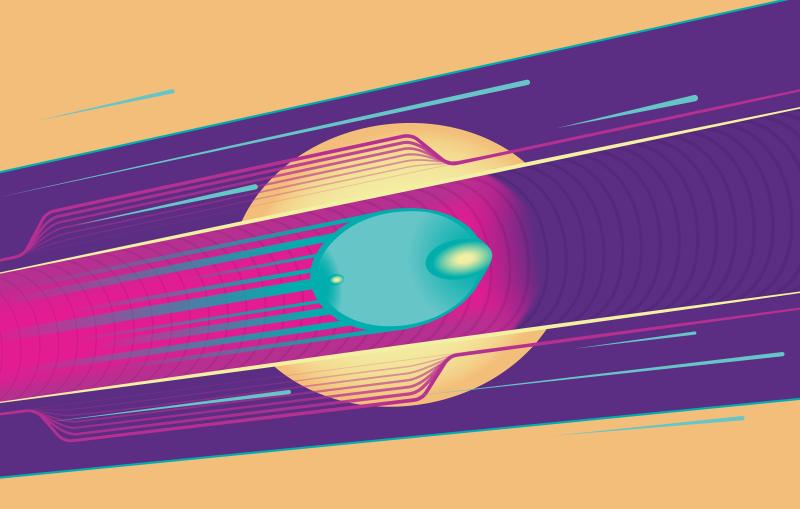

Poincaré beams combine multiple light polarizations – different directions in which light waves vibrate– into a single pulse that forms complex patterns. This allows scientists to study materials with one quick flash instead of multiple scans, saving time and capturing rapid changes in materials as they occur.

The team achieved this by using two separate sections of special magnets known as undulators, which wiggle electrons so they produce light. This generated two separate light beams, each with its own wave pattern and polarization. By carefully overlapping them, the researchers created a single beam with different polarization patterns across its surface.

The result is a stable beam whose distribution of polarizations stays unchanged as it travels. By adjusting the timing between the two component light beams, they caused the beam’s polarization to twist across its surface in a spiral-like pattern. They could then study this pattern and map where each type of polarization appeared in the beam.

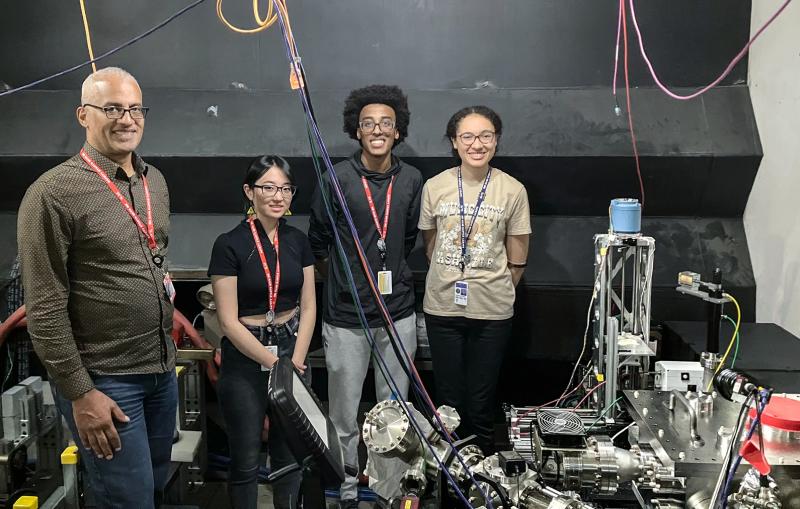

The concept originated years ago with SLAC scientist Jenny Morgan during her PhD work and was tested at FERMI, where the team had the flexibility to experiment freely with extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light.

“It’s exciting to manipulate complex polarization patterns at short wavelengths,” Morgan said. “EUV light can be harder to tailor than visible light, and at these wavelengths it opens up new possibilities for experiments.”

Although the experiment was conducted in the EUV range, the breakthrough opens the door to generating these beams at X-ray wavelengths in future experiments at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray free-electron laser, where the higher photon energies can reveal even finer details of atomic and molecular behavior.

“We’re planning to install a Delta undulator at LCLS later this year, similar to what we used at the FERMI facility,” Hemsing said. “This will give us more precise control over the polarization of the X-ray beam, allowing us to refine the technique and explore its potential at specific wavelengths, pulse energies and very short time scales. We’re also engaging with photon science, chemistry and materials science communities to identify applications. The goal is to study the machine’s performance and make this a standard capability at the newly upgraded LCLS.”

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: J. Morgan et al., Nature Photonics, 12 August 2025 (10.1038/s41566-025-01737-7)

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.